4. Calculating Moment of Inertia for Composite Areas

4.1 Introduction

In the second chapter, we learned how to calculate the moments of inertia for any given area and coordinate system using integration. The previous section introduced the Steiner's theorem.

With this knowledge, we can now calculate the moment of inertia for cross-sectional areas described by integrable functions, relative to the chosen coordinate system. This allows us to determine the moment of inertia, for example, for a rectangle, a triangle, a circle, or a quarter circle.

Additionally, by using the "Steiner components" of Steiner's theorem, we can calculate the moment of inertia for the centroidal axes of the area, even if they do not align with our chosen coordinate system.

Finally, the Steiner's theorem allows us to convert the moments of inertia with respect to any parallel axes by shifting them from the centroidal axes by the required distances.

With this knowledge, we are able to calculate the moment of inertia for cross-sectional areas that we cannot describe using integrable functions. The prerequisite for this is that such a cross-sectional area is composed of shapes that we can calculate.

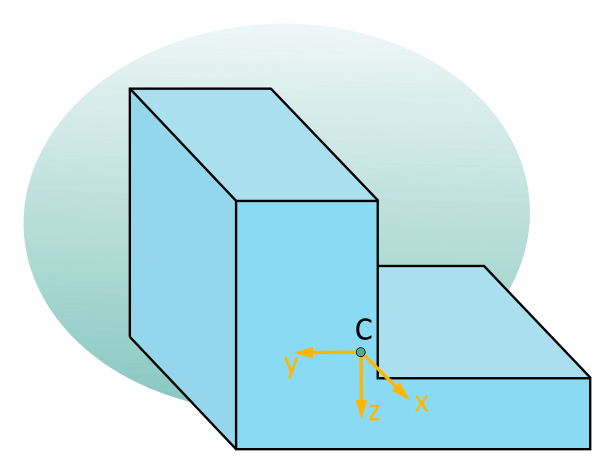

A simple example of such a cross-sectional area is shown in Fig. 6.4.1:

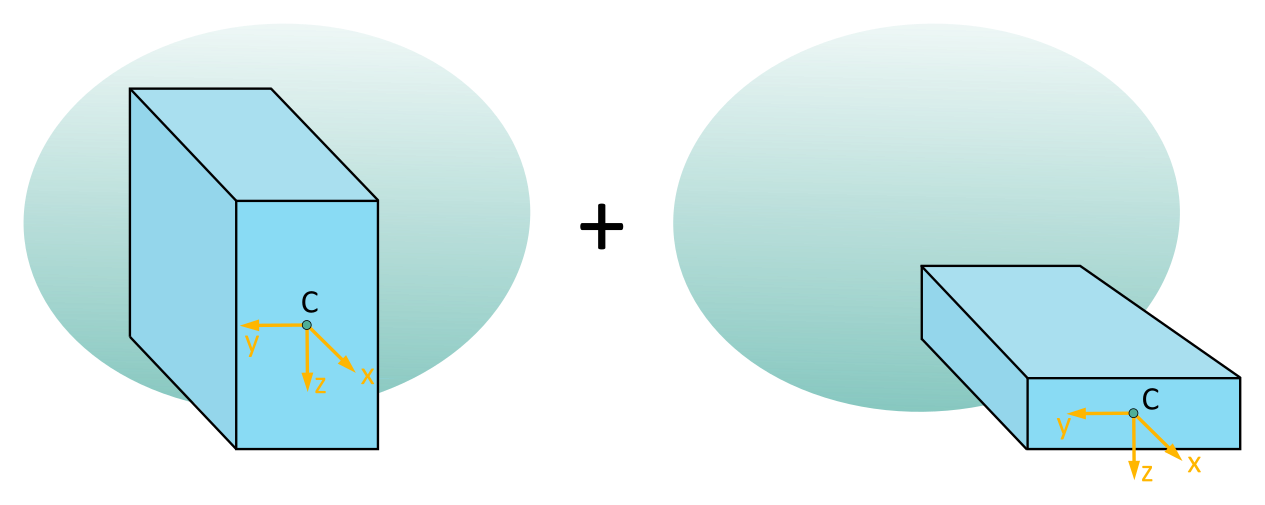

There are various ways to represent this cross-sectional area using simple assembled shapes:

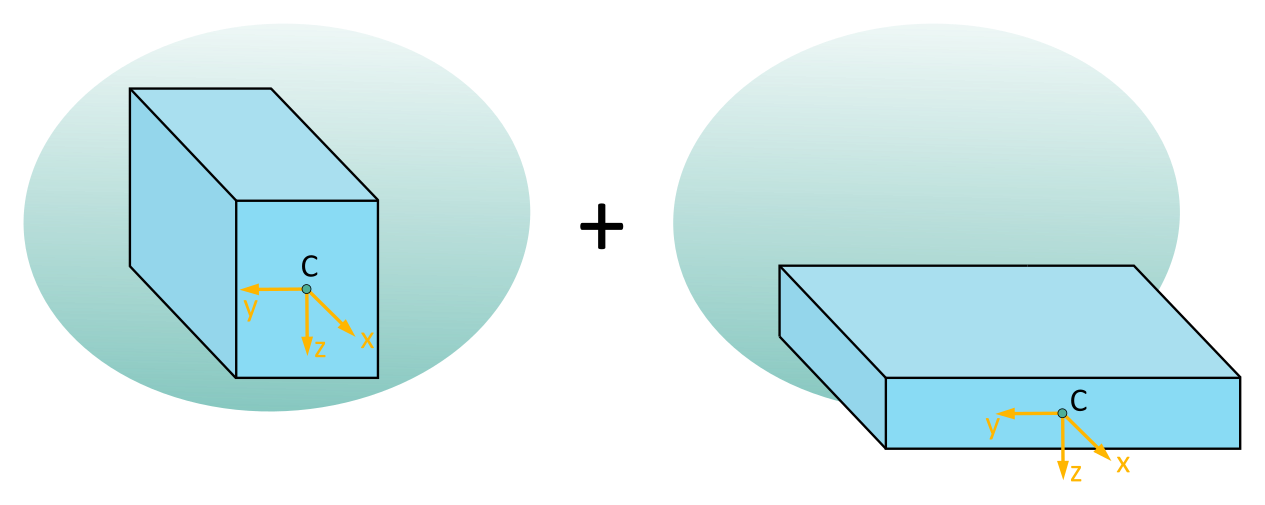

An alternative choice of rectangular areas is shown in Fig. 6.4.3:

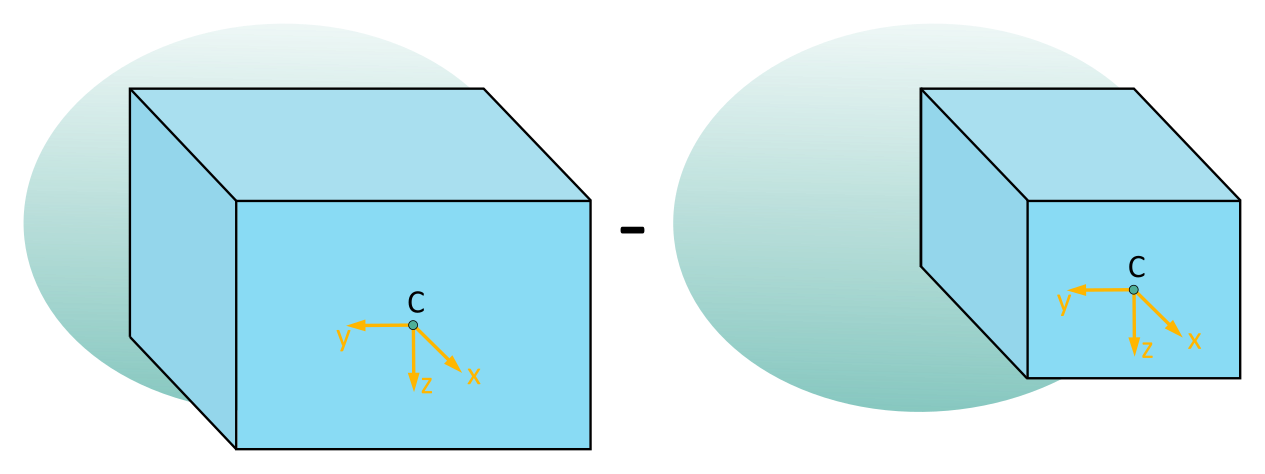

In addition to adding areas, there is also the option to treat cutouts as "negative" areas. They are subtracted from a larger sub-area:

Figures 6.4.2 to 6.4.4 describe simple sub-areas that, when composed (or subtracted), result in the L-shaped cross-section from Figure 6.4.1.

In the next step, we utilize the fact that we know or can calculate the moments of inertia at the individual centroids of the simple sub-areas to determine the moment of inertia of the composite area.