2.2 Normal and Shear Stresses at an Arbitrary Angle

In the last section, we learned how to calculate the normal stress when the cut is perpendicular to the axis of the bar. But what if the cut is at an angle?

Sure, two cuts perpendicular to the axis are easy. On both sides you have the same normal force \(N_x\). So to say: Everything is in the lot, everything is easy.

But doesn't it get more complicated if you choose the cutting angle arbitrarily? No! Remember: The system wants to stay in balance. Otherwise, the cut-off part would fly off - and where would that get us?

So: No matter how you cut, the force on the bar axis must be the same in both directions in the uniaxial stress state. Otherwise, the whole thing would move!

Oh yes, and the stress vector? It always shows you nicely where things are going. In the case of a uniform distribution of internal forces, it lies bravely on the x-axis. Besides, there are its components of normal and shear stress, but they are either at right angles to the cutting surface (normal, right?) or lie in the cutting surface.

It is therefore clear: In a straight cut, there is no shear stress in uniaxial loading, since the stress vector only consists of the normal stress component.

Why? Well, stress vector and its normal stress component lie on the x-axis! There is no stress triangle. So the shear stress is zero.

Let's imagine we have a cool cutting surface and we want to know how the stresses are distributed there. To do this, we need to rotate the coordinate axis so that it is perpendicular to the cutting surface. This creates our new \(\xi\)-axis (\(\xi\) is the Greek letter 'xi').

The cutting angle \(\varphi\) (see Fig. 1.2.3, Fig. 1.2.4) is so to speak the angle between the old x-axis and our new \(\xi\)-axis. Quasi a rotation of the x-axis to make the whole thing easier.

Quite simply: With this rotation we can calculate the normal and shear stress using a force triangle. This is a super practical tool for analyzing stresses.

In the force triangle we see three important forces:

- The resultant \(N_x\): This is the force that holds everything together. Direction of the stress vector. In the triangle the hypotenuse, i.e. opposite the right angle.

- The normal force \(N_{\xi}\): It acts perpendicular to the cutting surface and pushes/pulls the two cutting surfaces apart, depending on the prevailing load (tension/compression).

- The shear force \(Q_{\eta}\): It acts parallel to the cutting surface and tries to slide the two cutting surfaces against each other.

Remember the sign convention for normal and shear stresses? We learned that normal stress is positive if it points in the same direction as the \(\xi\)-axis. But shear stress is a sneaky beast! It can be positive or negative, depending on how we orient our coordinate axes.

To unmask the true face of shear stress, we need another axis: the \(\eta\)-axis (\(\eta\) is the Greek letter 'eta'). This axis lies in the cutting plane and is perpendicular to the \(\xi\)-axis.

The exact location of the \(\eta\)-axis depends on which coordinate system we used before the cut. Don't worry, this is usually not that difficult to see!

Once we have the \(\eta\)-axis, we can finally calculate the shear stress and determine its true sign.

But be careful: The sign of the shear stress does not change its physical property. No matter if it's positive or negative, it still describes the same force that tries to slide the two surfaces against each other.

Therefore, we don't really care - except in exams, where the correct sign of the shear stress can earn you points.

You know it: Sometimes it's just easier to look at things from a different angle. The same is true for shear stress!

Let's take the usual x,y-coordinate system for example:

- x-axis: Positive to the right.

- y-axis: Positive upwards.

What happens now if we rotate our coordinate system by the cutting angle \(\varphi\)?

- The shear stress \(\tau_{\xi\eta}\) (\(\xi\)-\(\eta\)-component), which results from the shear force \(Q_{\eta}\), has the same direction as the negative \(\eta\)-axis.

- Since the \(\eta\)-axis is positive to the top left, the shear stress is negative in this case.

But don't worry! This does not change the physical meaning of shear stress. It still describes the same force that tries to slide the two surfaces against each other.

- x-axis: Positive to the right.

- z-axis: Positive downwards.

This time the shear stress \(\tau_{\xi\eta}\) is positive like the shear force \(Q_{\eta}\), because it coincides with the positive \(\eta\)-axis direction.

- The sign of the shear stress depends on the chosen coordinate system.

- However, the physical meaning of shear stress always remains the same.

We want to calculate the normal and shear stress at an arbitrary cutting angle. For this we need:

- The normal force \(N_x\) in the direction of the x-axis.

- The cutting area \(A\) of the cut perpendicular to the x-axis.

- The cutting angle \(\varphi\).

- The forces \(N_{\xi}\) and \(Q_{\eta}\) in the \(\xi\)-\(\eta\)-plane.

- The cutting area \(A^*\)

This means:

To represent \(N_{\xi}\), \(Q_{\eta}\) and \(A^*\) as functions of the cutting angle \(\varphi\).

Normal and Shear Stress at an Arbitrary Section Angle

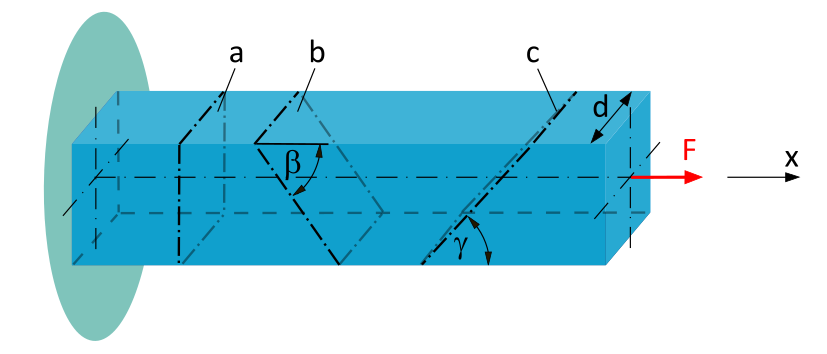

A clamped beam with a square cross-section (side length \(d=20~\mathrm{mm}\)) is subjected to a tensile force \(F=10~\mathrm{kN}\) along the beam axis.

Determine the average normal stress and the average shear stress...

- ...acting in cross-sectional plane a.

- ...acting in cross-sectional plane b (\(\beta = 50°\)).

- ...acting in cross-sectional plane c (\(\gamma = 40°\)).